The rain and cold mountain air were a welcome relief after nearly twenty hours in transit which included a flat tire on the sleeper bus, forced midnight dinner at a dirty rest stop and torturous Vietnamese music on repeat from the man next to me without headphones. We had escaped Hoi An and arrived in Dalat—a scenic yet bustling, mountainous countryside town full of greenhouses and french colonial architecture.

As we approached our hostel, a girl who worked there ran outside with a huge smile, jumping and celebrating our arrival as she pulled us in and sat us down at the family table. A group preparing food for dinner stopped to cheer and pound on the table, welcoming us into the family. Mama, the matriarch, ran out from the kitchen, took me in her arms with a giant hug, kissed my cheeks and shoved plates of fruit in front of me, commanding me to eat. It was almost as if they’d known about our bad experiences in Hoi An and were single-handedly trying to restore our faith in their people and make us never want to leave. They treated everyone who walked in the door with the same genuine enthusiasm and care, and it was as if fate had brought me here as I fell in love with this family and their charming town over the next few days.

We sat down to an early dinner that night alongside the other hostel guests as one big family at the dining table. Endless plates of rice and chicken and spring rolls and potato curry and veggies were served, followed by homemade banana pancakes which Mama continued to cook for hours until we were too stuffed to walk. Music and games were played as I made friends with new travelers and recognized others from somewhere over the past two months. The longer you’re on the road, the smaller the backpacking community becomes and eventually you’re almost guaranteed to run into someone you’ve met before in a new city. This is the time when it’s really becoming more interesting and fun.

I spent one day in Dalat navigating through a canyon. We hiked, slid and floated down rivers, repelled down waterfalls and jumped off cliffs into pools of cool water. It was thrilling and a great way to balance out Mama’s endless plates of banana pancakes.

My favorite experience was a motorcycle tour a friend and I booked. A Vietnam war veteran named Rafael spent the day driving us around through the city and countryside, stopping along the way to teach us about his land and the culture and history from his personal account and perspective.

Perhaps even more though, he was so eager to learn from us. He’d constantly ask about what we knew about the war and history, how to pronounce certain words, how to phrase sentences, scribbling notes in his notepad and asking us to write entries for him. He’d tell us about his struggle living in the south without any help from his country and barriers in place which made it difficult to live. He’d speak with sadness about the lack of opportunities for his children and make sure we knew how lucky we were to be born in a place of freedom and opportunity.

We stopped at a clearing where Rafael pointed out bare patches of mountain that had been destroyed with napalm during the war and the original jungle landscape was never able to regrow. We drove past farmland and greenhouses and construction sites, taking shelter from sudden downpours and stopping at a temple and waterfall and coffee plantation and silk factory and house of wild animals.

The chilly, foggy rainy mountain town of Dalat seems almost out of place in Vietnam. Outside of the city, the landscape of pine trees planted to replace the native jungle and fresh water lakes dotted with European style houses and upscale coffee shops made me feel like I could be in any other first world country. If I was going to live anywhere in Vietnam, Dalat would be home.

You never know what you’ll get when checking into a new hostel. It’s like starting life over every week, or every few days lately. There’s a feeling of suspense and anticipation, jumping blindly into a new environment and experience you’ve never encountered and will never encounter again.

I had no idea what to expect when walking down that alleyway in search of Dalat Family Hostel, but as they hugged and kissed me goodbye a few days later, I knew that this place was as good as it was going to get. They became one of my fondest memories in Vietnam and some of my favorite people in this world. Within ten days I’d experienced the best and worst of Vietnam on the human level, and it was time once again to move on.

Ho Chi Minh City (aka Saigon), the capital city, was another long bus ride away. At nightfall we boarded a sleeper bus at the station and were awoken at 3am where they kicked us off into the streets of Saigon into a crowd of awaiting taxi drivers. We navigated one of them to our hostel and twenty minutes later we’d arrived, dragging our heavy backpacks and tired bodies up the steps to reception. Check in wasn’t for eight more hours and there weren’t any rooms available, so we passed out on bean bags in the non-air conditioned waiting room alongside others with poorly timed transportation (it was actually more comfortable than any dorm bed I’ve slept in yet).

The next morning I had important matters to take care of at the notary (after a confusing and unsuccessful day in Dalat) and the hostel receptionists didn’t understand my request, so I was on my own with Google maps as my only source of hope. I located several buildings that could potentially be notaries but it wasn’t clear, so I chose one and hoped for the best. I decided to walk, taking my time to see the city and perfect my pedestrian traffic navigating skills in the most chaotic roads in Asia.

Nothing was in English when I walked up to the building so there wasn’t anything to indicate if I was in the right place aside from people behind a desk stamping papers, so I could only assume. I pointed at my documents and asked “Notary?” hoping they’d be the first Vietnamese people I’d spoken to in the past week to understand this word. Instead I received blank looks as they passed their confusion onto each other until settling on the most fluent English worker, who simply pointed to the door and said something that resembled “Up”. With a glimmer of hope in my future, I walked upstairs to the next level, entered another room that looked just like the first one, and the same scenario played out. Finally I made it up to the third level, entered a room that looked more official with just a few Vietnamese workers and handed my papers to one of them, pleading for help. He looked them over and finally spoke, with just enough English words for me to understand, “We can’t do. It in English, we sign Vietnamese paper only. You can go to US Embassy”. Sigh… back at square one. I didn’t have my passport on me of course, so I walked back to the hostel, Googling the closest US Embassy on the way. It was not in walking distance and daylight was running out, so I had no choice but to jump on the most trustworthy motorbike taxi and brace for the insanity that was about to ensue.

If you’ve never been in Saigon traffic, it’s not something that can be put into words. You can watch the footage and try to imagine yourself in that position, but it just doesn’t elicit quite the same “I’m going to die at any second” rush. I clutched my backpack with one hand and held onto the seat for dear life with the other, knuckles white the entire way. My legs were tensed and pulled in closely to the bike, as any movement in any direction could be clipped by a passing bus or car. Then a bike with a mother and her two young children appear on my right, and they’re smiling and relaxed as if completely unaware of the certain death they’re mere inches from—their fate in the hands of the thousands of drivers surrounding us. And it boggles my mind that this is everyday, normal life for these people.

I make it to the embassy, grateful for another chance at life as I rush to the entrance hoping this stressful journey was not in vain. Turns out you need an appointment first, and there was nothing they could do. It was Friday afternoon, the embassy was closed on the weekends and I was leaving for Cambodia on Sunday. At this point it had been almost two weeks and three cities trying to complete a task that would take 20 minutes back home (I’d been trying since Hoi An). Don’t expect to get anything important done in a timely matter here.

With my efforts exhausted, I finally gave up, found a (car) taxi, and treated myself a cheap mani/pedi to least somewhat salvaging my day of accomplishing absolutely nothing.

We joined a couple friends I met back in Bangkok on my first day and they decided to rent motorbikes to travel to the Cu Chi tunnels. I wasn’t thrilled with this idea after my experience the day before, but it was a better way to see the city than a two hour public bus ride and promised to deliver more adventure, so we decided it was worth the risk and hitched rides with them. For the first twenty minutes I did my share of second guessing this decision, but then at some point it becomes not so terrifying. Then it becomes okay and normal. Then it becomes fun and exciting. And then you understand how people who grew up this way don’t give it a second thought or worry about transporting their infants or pets or anything of value to them, because they know there’s no sense living in fear, and they trust that somehow, it just works. Eventually I began to trust too—becoming one of them, releasing my fear and living in the moment, and it was my best memory in Saigon. I’ll remember that feeling forever. And once again, I learned that’s what happens when you let go.

Everything I’ve known about the Vietnam War until this point had come from history books and second or third hand accounts of friends and relatives involved in some way. It’s never truly affected me personally or been an influencing factor in my own life. I was looking forward to this part of Vietnam—to seeing the effects of the war generations later, speaking with those involved and witnessing how it has impacted the people their and feeling towards Americans.

In Hanoi I experienced my first glimpse of this. People with no legs on the street begging for money, others with crippling deformities in wheelchairs paraded in front of tourists to elicit sympathy (and guilt for Americans) as a result of chemical warfare. A firsthand look at the residual effects of the agent orange we poisoned them with for years. This could be a scene from any city somewhere back home, but here it’s very different because it’s not from random genetic mutations or accidents or misfortune—we purposely caused this. We are responsible for this.

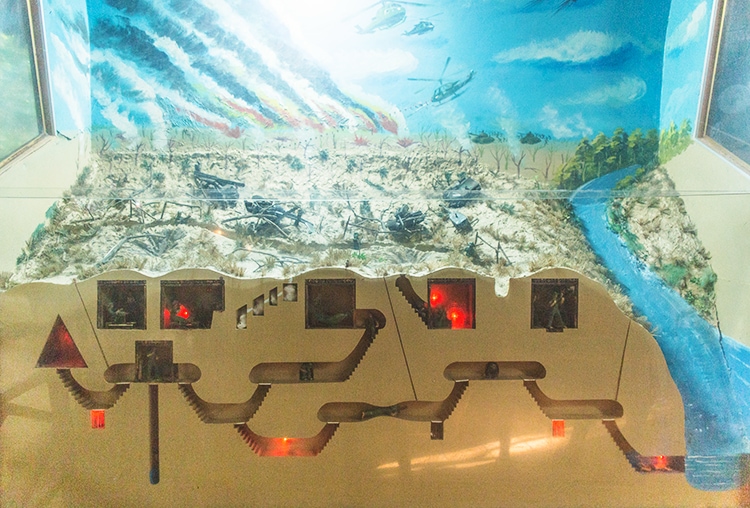

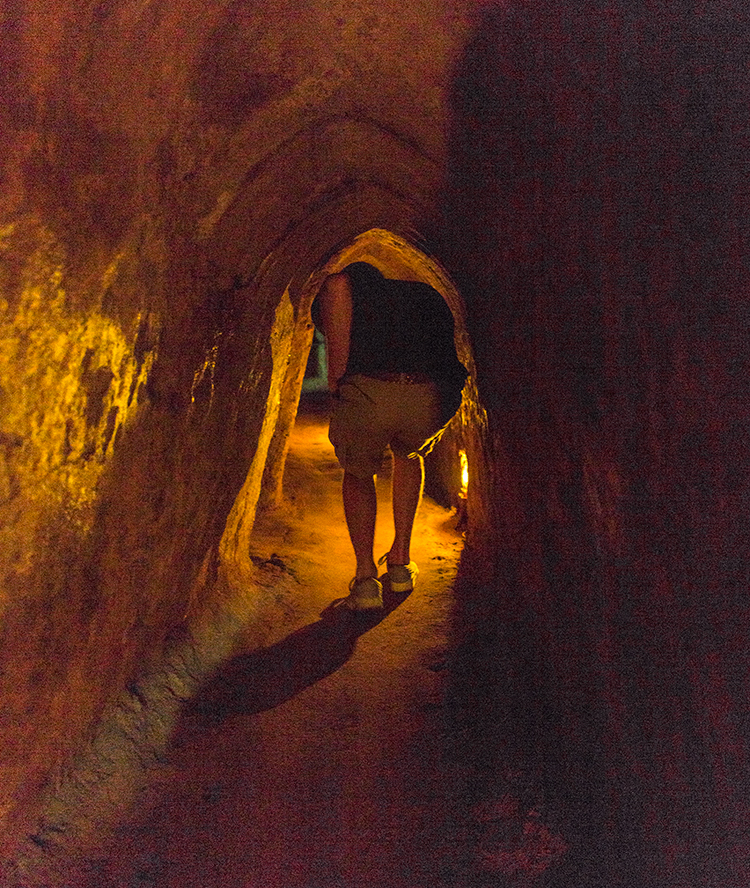

During the war, the Vietnamese constructed elaborate underground tunnels as their only defense and means of survival. We visited the Cu Chi tunnels, standing on the same land so many took their final steps on four decades ago. We squeezed our bodies through the narrow passageways and crawled through dark tunnels, the ancient dirt sticking to our sweaty skin as bats brushed our heads as they flew by. We walked through the storage bunkers and meeting rooms where military leaders devised plans to defeat the enemy and saw the elaborate spiked traps that took American lives. We shot M19’s and AK-47’s in their practice ranges and watched grainy black and white footage of smiling and dancing local villagers mixed with bombs and upbeat, lighthearted music. It was an interesting experience, and another way to gain insight into this culture’s sentiments about America, and provide a better understanding of the way they view us.

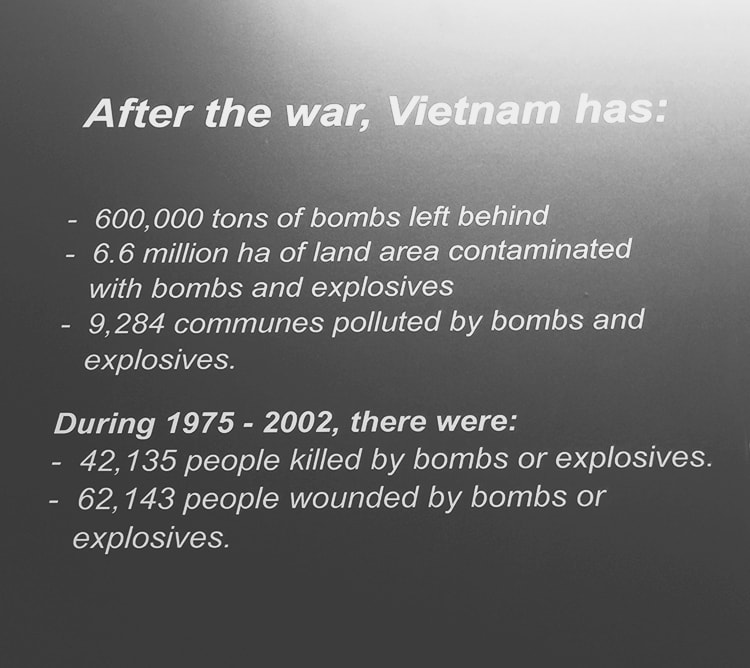

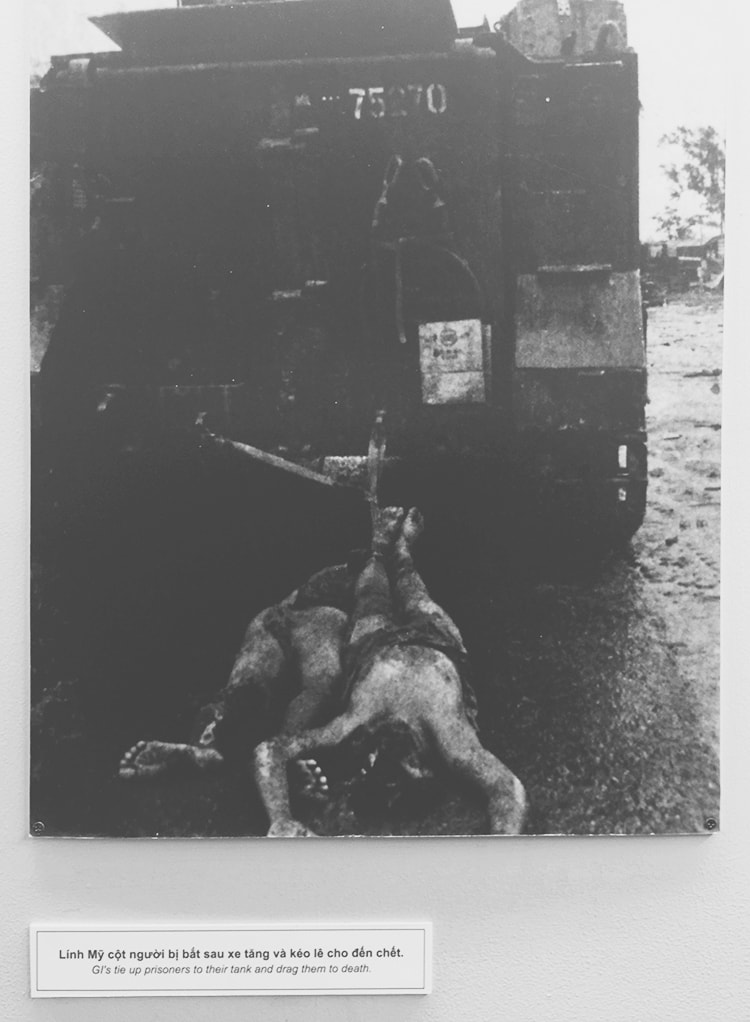

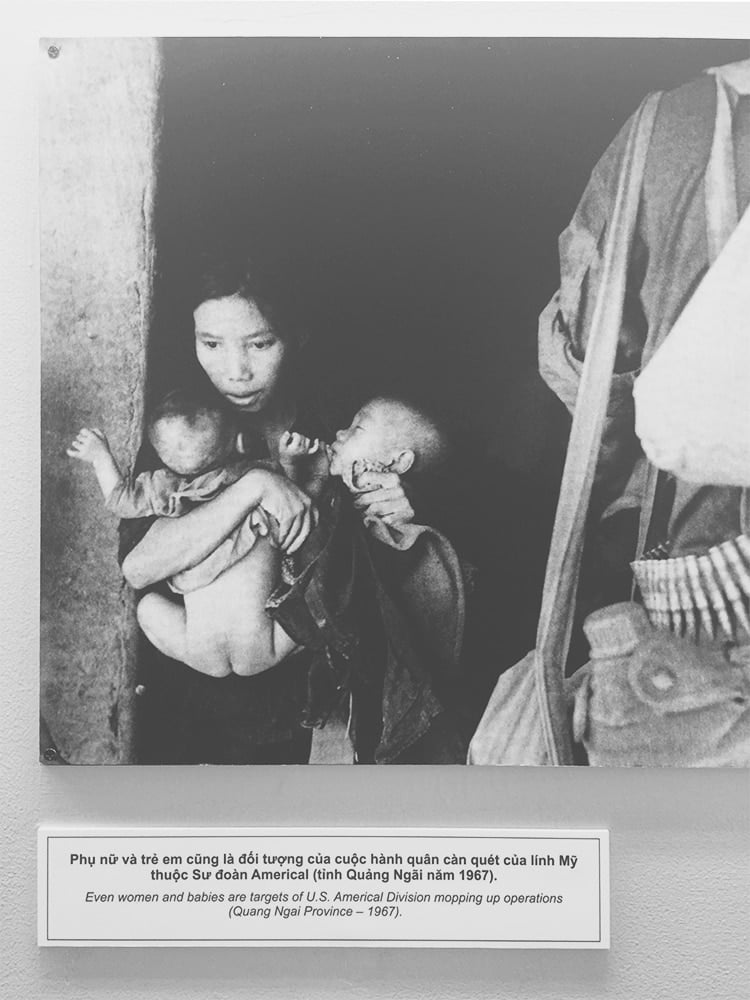

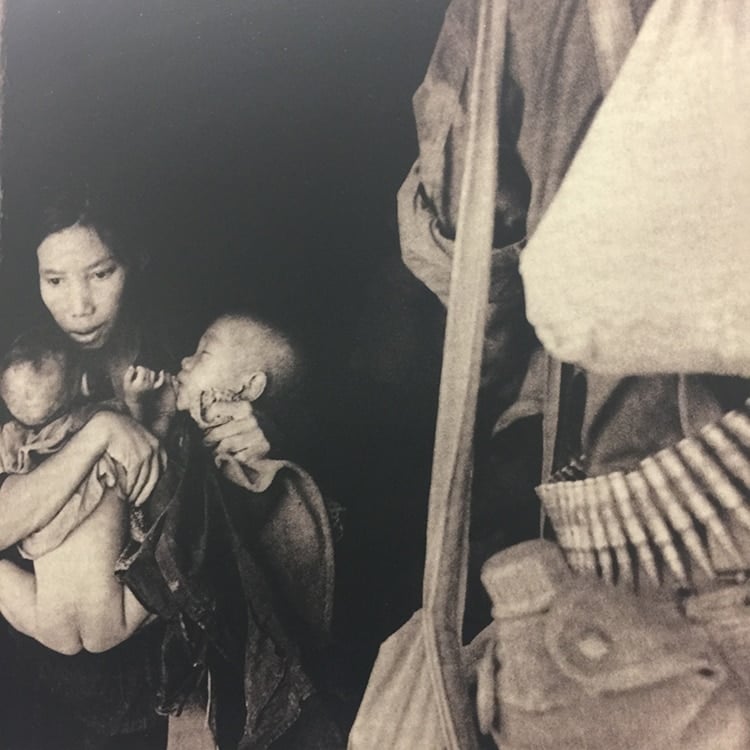

The next day we visited the War Museum, spending hours taking it all in. Many photographs are ones I’d seen before, but the stories behind them are what really stood out. So many lives were destroyed, so many families lives ruined in this ugly, devastating war. And for what? There’s an entire room dedicated to agent orange, plastered with photographs of generations of mutilated victims, still being born to this day. There’s a lingering effect of mistakes made decades ago and they’re still paying for it. Veterans with the trauma that will never leave their minds are present here, passing on stories to others. No wonder they don’t all accept us with open arms. I’ve personally never had any negative encounters stemming purely from the fact that I was American, but I’ve spoken to others who have—locals who have changed their demeanor and refused to look at or speak to them once they revealed their nationality. It’s not right, sure… but I can acknowledge that as much as I try, I’ll never be able to put myself in their shoes and really understand what they’ve been through to make them feel this way. So rather than judge, I thank them for the learning experience.

I was walking down a well traveled street back to my hostel when I reached into my purse to grab something. Out of nowhere, a motorbike raced by, yanking it right out of my hands and was gone the next instant. I had no time to react, but luckily since it was open my phone managed to fly out and land in the gutter. It was shattered and broken but he didn’t get away with it. I had just gone to the ATM so he had all my cash, but that was it.

After the initial shock wore off, naturally I became frustrated and angry. But then… I got over it. I had my phone and my life. It could have been worse—like the girl who had her bag wrapped around her and was dragged through the street instead. The motorbike thief wasn’t born with the same good fortune and opportunity I’ve enjoyed my whole life, and his situation is bad enough that he felt he had to resort to taking from tourists who can afford it. If that money is feeding his family or aiding in his survival in some way, it’s better spent there than funding this trip for me. So I continued walking home, $140 poorer, purseless and making sure to hide and/or hold on to my belongings much tighter from that day forward. It’s easy to keep your guard down when that’s always been your way of life and you aren’t used to constantly having to look over your shoulder and view everyone as a potential threat. It’s not a switch you can just flip on—it develops over time through unfortunate experiences like these. Even if you’ve heard the stories, it doesn’t really sink in until it happens to you. It’s a slow shift in your mindset and I’m slowly getting there. I’m definitely more aware of my surroundings and the location of my belongings, though bad things can happen to anyone at any time. It’s not always in our control… and I am still learning to let go and embrace that.

Overall I really enjoyed Saigon and, as with every place I visit, it flew by way too fast. Between getting caught up in its infamous traffic jams, exploring the outlying villages and rural farmland via motorbike, seeing a bit of the nightlife and shopping markets, a firsthand account of the war and encounters with the locals which prompted change within me, it was a very full few days and a perfect way to say goodbye to what has been my favorite country so far.

Adventures from Cambodia, coming up next…

Amy says

This is completely unrelated to this post and you probably don’t even care at this point, but I was pleasantly surprised when I got my new issue of HGTV magazine to see your kitchen cabinets featured in a kitchen chronicles article. Congrats!

jennasuedesign says

Very cool, I’ll have to check that out! Thanks for the heads up.

jan says

You are such a gift to us! With your compelling photography and gift for story telling we are able to see and feel places we will never see.

linda says

It is great to see you travel with such humility and respect for the people and cultures you experience. I’m sure you already know that there is no learning experience equal to travel. I’m a busy mom now, but spent a lot of my younger life travelling. So good to live life wholeheartedly, outside the comfort zone. Thanks for sharing your adventures!

Deborah says

The Vietnamese were not the only ones effected by this war. They too did awful, unspeakable things to Americans. Being an American is something to be proud of. We are the greatest nation in the world.

Shelley says

Having been elementary school age during the Vietnam War, I grew up watching it on the evening news. It was so difficult to understand what was happening and unbelievable. These images bring back memories and a little more understanding. We must never underestimate the impact of war on all parties. Thank you for sharing.

deb says

I’m just curious about when you’re coming back to the states? Enjoying the series, BTW!

Michellw says

My father served in Vietnam and was sprayed with Agent Orange ( they do consider anyone serving from something like 67′ to 72′ as getting sprayed)…he ended up dying from prostate cancer and had diabetes, both of which are known to be caused by being sprayed. He was also a VERY violent human being who suffered from ptsd and extreme anger issues…all of which were passed down to his children in some way. I have ptsd due to all the many violent acts I had to see as a child. My sister has a spine deformation that is linked to being sprayed.

All in all…Americans and Vietnamese got screwed and it’s disgusting.

jennasuedesign says

That is horrible. I’m so sorry it has affected you on such a deep, personal level. No one wins in war.

Amy says

I hate that for you. My uncle has heart issues from the Agent Orange. My cousin has a deformed hand from a helicopter crash. One of my inlaws has PTSD and still can’t bring himself to talk about the war. You are so right, the Vietnam War hurt so many on both sides. So sad.

Emma | banquets and backpacks says

I understand how you feel to have negetive experiences in Vietnam but still consider the country to be a favourite. Vietnam is where adventures are born but Cambodia has a little more soul I think.

jennasuedesign says

Great way to put it. I’ve definitely found that to be true so far of Cambodia!

Lu Ann says

Loving your adventures and traveling along with you! Looking forward to Cambodia!